Hastings’ Own ‘Little Coney Island’

October 27, 2021

Reprinted from the Summer 2021 issue of the Hastings Historical newsletter. All images courtesy of the Hastings Historical Society

Located in the borough of Brooklyn, the original Coney Island is a neighborhood that is synonymous with fun. It has an inviting seaside beach, a busy boardwalk full of vendors hawking hot dogs and icy treats, and an amusement park that is home to the famous Cyclone roller coaster. Opening in 1895, it was wildly popular and several parks under the name of “Little Coney Island” were established in the New York tri-state region in the early 20th century. This article is about the one in our area.

From 1900 to 1912, at the southeastern edge of town, was

Hastings’ own amusement park: Little Coney Island. A popular weekend destination, the one-acre park was situated along the Saw Mill River, as several visitors recalled a dance floor straddling the water. However, Little Coney Island’s exact location

is hard to pinpoint, although there are mentions of it being “at the Saw Mill River Bridge on Farragut Road.” In the Historical Society’s files, local resident Thomas J. Pyne attributed

this difficulty to the relocation of the river in the 1920s, which was done in order to accommodate the Saw Mill Parkway. Evidence indicates that today’s parkway travels over at least a portion of the land that once contained this amusement park.

Martha Paige, Mrs. Joseph Mungavin, and Ted Hogan recall childhood visits to Little Coney Island with their fathers. Edwin P. McIntyre, another former park-goer, once thought of writing a musical about the subject. The attractions these Hastings residents remembered include a “huge” (and free!) steel slide called the “Zippo,” a carousel and pony rides for the children, a small bathing beach with a special area for children, a shooting gallery whose water-wheel-powered moving targets were shared

with the adjacent throwing booth, a hot dog stand, and a

“notorious” saloon.

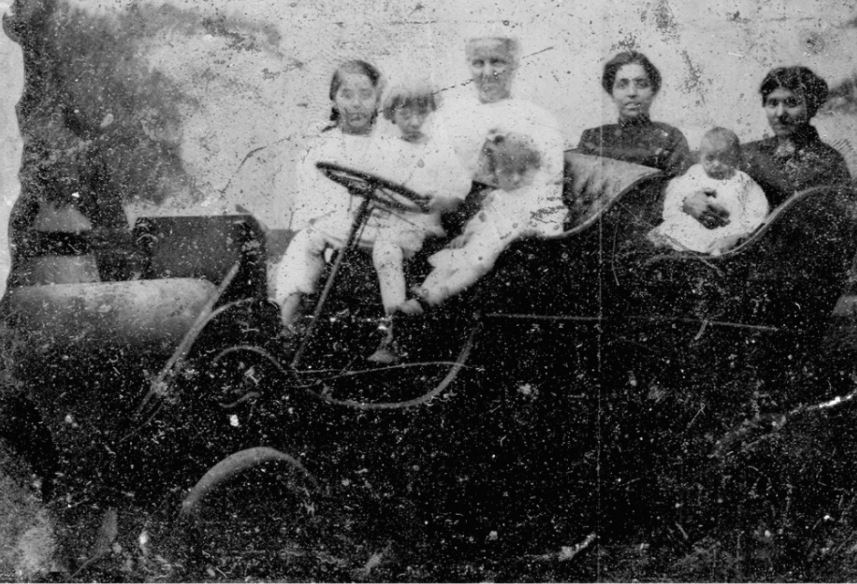

In addition, there seems to have been a resident photographer at Little Coney Island, who visitors could pay to take

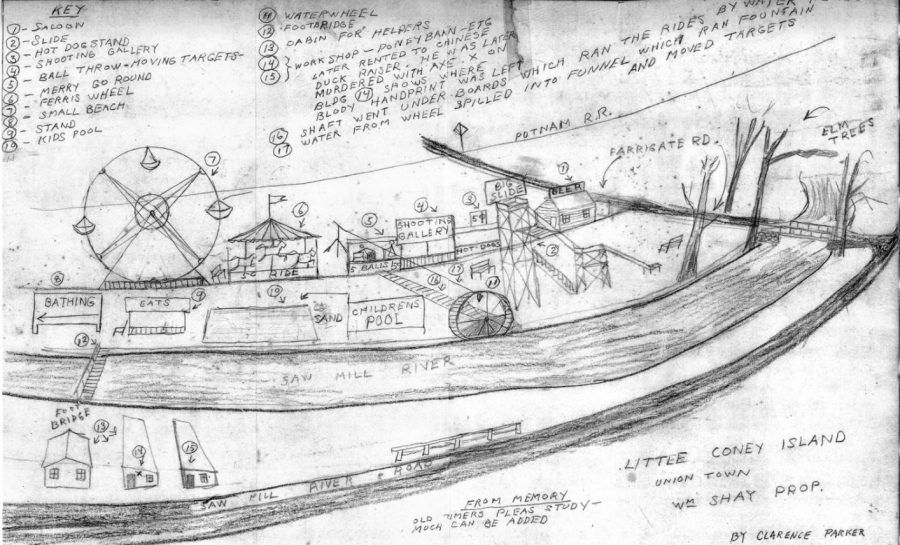

their portraits. The Historical Society has possession of several tintypes from the amusement park, which show visiting groups posing for the camera. The remembered attractions

and others can be seen in a hand-drawn map of the amusement park created by former Hastings resident Clarence C. Parker. The map was made from memory approximately 70 years after Little Coney Island’s closing in 1912. Besides the attractions, it depicts the site of an axe murder that occurred on the property years after the park shut down. The background on that story is that the space formerly occupied by Little Coney Island’s pony barn was later rented to a duck farmer, who was murdered nearby.

The amusement park was seasonal, open only between May and September. Little Coney Island had so many visitors during the summer months that a local paper of that time, the Irvington Gazette, wrote that the park’s three ponies must have been longing for winter, as they were constantly working while the children were out of school.

While Little Coney Island was recognized as a family attraction

during the day – and was within easy walking distance of most of

the Village – the amusement park became off-limits to Hastings’ girls after dark. Indeed, due to its shady reputation, attributable to drinking behavior at the saloon and what was said to be the unsavory conduct of proprietor Bill Shay (sometimes

spelled “Shea”), Hastings parents were wary of allowing their children to visit at all, making the place far more popular with those from out of town.

Park-goers often came from New York City, some by car, but most

arrived via the New York Central’s Putnam Division, better known as the “Old Put.” The Nepera Park station was just a short stroll away from Little Coney Island. (The track of the Old Put was located where the South Country Trailway is today.) The destination was so popular that the New York Central reported carrying 40 carloads of visitors to the amusement park on the weekends, although this is likely an exaggeration, as the

park’s single acre could hardly fit thousands of people.

Visitors, local and more distant, could also take the Uniontown trolley, a streetcar that traveled through our Village and had its

terminus a few blocks away from the park. The Uniontown trolley connected with the Yonkers #1 trolley; at Getty Square, there were connections to other villages in southern Westchester. Starting in

1908, a day-tripper from New York City could travel to the newly completed subway station at 242nd Street in the Bronx, then transfer to a series of trolleys that would get them to Uniontown. Thus, for a few years, there was a low-cost (although lengthy) alternative route for city residents to travel to Little Coney Island.

“Goldbutton” Bill Shay, the amusement park’s first proprietor, seems to be a large part of what Hastings residents remembered of Little Coney Island years after its closing. Said to be “a character,” Shay received his nickname from wearing 10-dollar

gold pieces on his waistcoat in place of buttons. The Historical Society’s files also suggest that Shay may have owned a shoe store in Hastings. According to Thomas Pyne, “He was way ahead of his time. He was a real weirdo, hair over his shoulders and he could stand a bath.”

Among Shay’s amusements was one “not too amusing,” involving an artificial country pump. As people went to grab the pump’s handle for water, they suddenly could not let go. The pump did not actually access water; instead, an electrical current ran through it that stunned, but did not physically harm, visitors who fell victim. Sympathetic onlookers would try to help the victim and get caught in the electric current by touching them. The joke went on until a human chain of about 10 formed, at which point the manager would turn the power off and reveal that it was a game all along.

Shay was also remembered for a trick he would often perform for visiting boys, where he created the illusion of poking a finger through their caps. Although Shay looms large in residents’ recollections, he reportedly passed management of the park to the Rantf brothers (also spelled “Ramft”) of Hastings in 1911. It is unclear why, although mental instability may have played a role.

Four years later, in August of 1915, Shay was committed to the Hudson River State Hospital in Poughkeepsie after being judged insane for beating his wife on the head with a hammer. As a patient there, he enjoyed what was considered a life of luxury for mental patients, as the hospital was at the time a shining example of American healthcare reform, allowing residents like Shay to enjoy recreational activities and explore their expansive grounds. We have little information of what happened to Shay after his commitment to this institution.

About a year after Shay handed management off to Frederick Rantf and his brother, Little Coney Island closed following its 12th year of operation. There are several differing accounts regarding the causes for the closure, although it’s clear that local opposition was a major factor. One states that riotous behavior, likely brought about by excess drinking at the amusement park, led to its ultimate demise. The park garnered much criticism under the Rantf brothers, who received multiple noise complaints from neighbors frustrated with the racket coming from the merry-go-

round and beer hall.

When the Village failed to address the residents’ frustrations, they approached the District Attorney, who insisted that the Hastings-on-Hudson Village Board require a $5 per day operating license for Little Coney Island’s merry-go-round. Frederick Rantf applied for such a license on August 10, 1912. The application was refused, forcing the amusement park to close. Some also cite a merry-go-round incident wherein a girl broke a limb as the reason for the

1912 shut down. Following the amusement park’s closing, the area became a popular hangout for swimming. Then, when the Saw Mill Parkway came through in the late 1920s, the terrain changed, erasing all vestiges of when Hastings’ “Little Coney Island” was a destination hot-spot.

Ken • Nov 17, 2021 at 6:37 am

WOWZAH! Born/raised in Coney, nevah knewthis