Here’s Why You Should Believe in St. Nicholas

A Perspective

An 1863 depiction of Santa Claus. This cartoon, by Thomas Nast, is considered the first modern depiction of Santa Claus.

December 18, 2021

St. Nicholas, the Catholic and Orthodox saint who served as inspiration for Santa Claus, allegedly slugged the Christian heretic Arius in the face at the First Council of Nicaea in 325 C.E.

Did this really happen? It is difficult to say for sure. Like most early Christian saints, St. Nicholas is an obscure figure whose life is a blend of history and legend. We do know certain things about his life. He was probably born to Greek parents in Turkey, which was under the control of the Roman Empire, and was orphaned at a young age. Pious from childhood, he became a Christian monk. Such was his renown that he served as the Catholic bishop of Myra, in Turkey. He was probably imprisoned by the Roman emperor Diocletian. Beyond this, we know little for certain.

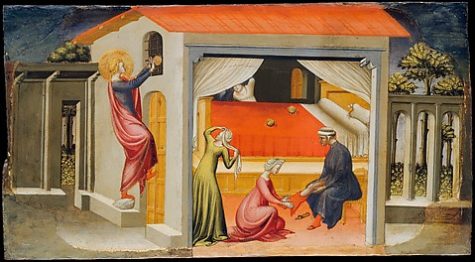

Many legends exist about his exploits. Despite the incident at the Council of Nicaea, most stories involve St. Nicholas, the holy orphan, caring for vulnerable children. In one dramatic tale, St. Nicholas revived three boys who had been cut apart by a murderous butcher. Another story — perhaps the most significant story about the saint — served as inspiration for Old Kris Kringle’s most beloved hobby: delivering presents after clambering down the chimney. According to legend, St. Nicholas threw three bags of gold through the window of a house where an impoverished father was about to sell his three daughters into prostitution.

To my mind, this story is one of the most inspiring stories from the early Christian period. It is Christianity in its purest form. St. Nicholas used money not for self-enrichment, but for charity. In a time before greedy bishops stored away enormous sums for the purpose of empire-building, St. Nicholas decided that the best use of his money was to lift people out of poverty. Significantly, he also used it to bolster the dignity of women in an era when the Roman fathers had the power of pater familias, which gave them absolute authority over the women in their households.

St. Nicholas died in Myra, but his story did not stay there. In pre-Christian Netherlands, a magician was said to roam the land, bring presents to good children and punishments to disobedient children. As the Dutch people became Christian, this folktale melded with another legend about a kindly old man (who fit nicely with the Christian saint, St. Nicholas) to form Sinterklaas. Anglicized by Americans to “Santa Claus,” this jolly old man took on his present form after Thomas Nast, a famous political cartoonist, drew Santa Claus as a happy, bearded man in a red coat in an 1863 edition of Harper’s Weekly.

Santa Claus evolved to suit present tastes. Americans, a product of the modern market economy, still buy generously for each other. According to Statista.com, Americans expect to spend an average of $886 on Christmas presents this year. But somehow St. Nicholas’ soul is often missing from the frenzy.

St. Nicholas’ world was a lot like our own. His nation, the Roman Empire, was in serious turmoil; 75 years after his death, it collapsed. Old social structures were imploding, and the burden fell predictably on the poor. As his world collapsed around him, St. Nicholas could have used his power to create barriers between himself and the greater suffering community. Instead, he gave generously. What else was there to do? He could not stop the pain, but he could try to help. His story should sustain us as we inherit a plague-ravaged world bracing for the blows of climate change and famine. Give your heart to those who need it, even when all seems hopeless.