How Schools Abroad Are Reopening

October 11, 2020

COVID-19 has forced over 60% of schools worldwide to close and 1.5 billion students to stay home. With so much discussion over how best to approach reopening schools in Hastings, lessons can likely be learned by seeing how other schools are doing it. Almost all reopening plans overseas share some similarities with those here in the U.S., with smaller class sizes, social distancing, and personal protective equipment forming the backbone of them. Yet each country is also moving forward with some slight differences, a handful of which are described below.

Denmark

Denmark was the first western country to reopen its schools, doing so as early as April 15th. It chose to reduce its class size and continue in person teaching for students ages 2-12, but did so by assigning each student to a seperate “bubble” of 12 students. Each of those bubbles arrived at school at different times, ate lunch separately, and played in designated areas of the playground. Teaching also largely took place outside, as public parks were reserved for classes from 8:00am to 3:30pm. Similarly to Hastings, parents were not allowed into the school except for special cases.

Teaching also largely took place outside, as public parks were reserved for classes from 8:00am to 3:30pm. Similarly to Hastings, parents were not allowed into the school except for special cases.

Interestingly enough, neither students nor teachers were required to wear face masks. Desks were still two meters apart and up until recently students also had to wash their hands every two hours, but personal protective equipment was only recommended.

According to Dorte Lange, vice president of the Danish Union of Teachers, the government’s role was mostly hands off after setting the above guidelines. Cooperation between the school, teachers, parents, and local authorities was most important throughout the process in order to keep schools safe.

Israel

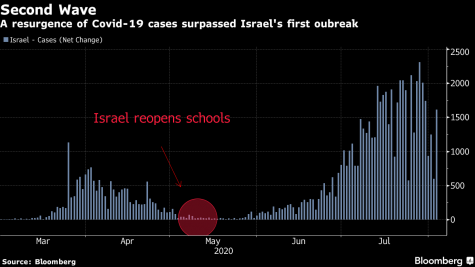

Israel followed a similar approach to Denmark in May, using a sort of “bubble model.” However, limitations on class sizes soon stopped, and students were allowed to leave their masks at home during a heat wave. This sense of security was likely due to the fact that a strict quarantine had brought daily new cases down to just a dozen a day, and people felt it was safe to reopen completely. However, just a month after these restr ictions were lifted, Covid-19 cases surged. The Israeli government was forced to shut down schools as hundreds of students and teachers were getting sick.

ictions were lifted, Covid-19 cases surged. The Israeli government was forced to shut down schools as hundreds of students and teachers were getting sick.

According to Eli Waxman, a professor at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, the country was unprepared to deal with a Covid-19 outbreak. There was no plan for stopping spread, or to isolate cases and trace contacts. Since then however, things have changed. The responsibility for building a strong contact tracing system was moved from the Health Ministry to the armed forces. Additionally, many are arguing for a more gradual plan with safety measures, where younger grades come in first in small groups, and higher grades will follow if no outbreak occurs. As of now though, Israel has gone back into full shutdown, so it’s yet to be seen how successful this reopening model will be.

South Korea

South Korea, infamous for its long school days and high workload, adopted an equally intense system when reopening its schools. Schools were only allowed to reopen after daily Covid-19 cases dropped below 50 per million people, and as soon as a student tested positive, classes went totally online. Temperature checks were implemented, in addition to masks, social distancing, and frequent hand washing. Students went in on alternating days, and for the first two months that schools reopened, there was no increase in cases in minors.

However, after a growing number of cases reached 300 per day, all schools were forced to return online, and it looks like that’s the way they’ll stay. Choi Won-hwi, who works in the South Korean education ministry, said, “we prepared for remote learning because of the Covid-19 crisis, but now it will be a permanent part of the educational process.” Indeed, these changes to the education system will be put in place in the anticipation that Covid-19 will stay for a while longer, and to protect against future pandemics. Just last week, the government invested over $110 million into making schools more digitally friendly. That includes developing online textbooks, installing wifi at schools without it, and providing hundreds of thousands of new computers and tablets.

The country’s major telecom providers have given free access to students accessing educational sites on their phones, at the government’s request. South Korea also refocused its education system around a government-run online portal called Edunet. On this site, all students can watch online lectures and submit homework, unlike in the US where only wealthy private schools are livestreaming their lectures.

Italy

Italy was the first epicenter for Covid-19 outside of China, but had managed to get the virus under control using aggressiv e testing and strict lockdowns. Even though cases are now starting to rise again, schools reopened in September. Like many other countries, teachers wear masks and face shields, and students are required to wear face coverings. Students and teachers don’t have to get tested before returning, but schools do need a designated room to isolate people who are suspected of being sick. If a student does test positive during the term, schools may briefly shut down before reopening, but this decision will be left to the local authorities and not the principal.

e testing and strict lockdowns. Even though cases are now starting to rise again, schools reopened in September. Like many other countries, teachers wear masks and face shields, and students are required to wear face coverings. Students and teachers don’t have to get tested before returning, but schools do need a designated room to isolate people who are suspected of being sick. If a student does test positive during the term, schools may briefly shut down before reopening, but this decision will be left to the local authorities and not the principal.

Whenever possible, classes will be held outside in parks, or in large buildings like museums, theaters, and churches. Classes can either be fully in person or alternate that with remote learning, but the government is not letting schools teach all their lessons virtually, stressing the importance of getting students, especially younger ones, back in the classroom. Socially distancing between desks will be enforced, but only to a distance of one meter.

Many are unhappy with this plan though, including The School Priority Committee —a protest group backed by unions that is calling for major changes to the entire education system. They point out that distance learning is not accessible to many students and teachers, leaving them at a disadvantage, and feel strongly that “schools must decrease, rather than increase, social inequalities and must absolutely not lose quality of education or students.” Their concerns are legitimate, as Italy’s public school system is poorly funded and might struggle to keep up with the new regulations and protective gear requirements.