The History and Myths of Affirmative Action

October 12, 2020

Affirmative Action. I have never found a more complex term that has meant so many different things to so many students. The grounds and history of Affirmative Action are poorly understood by many, so I set out to determine the fallacies and misconceptions of it and bust these harmful myths.

Affirmative Action was originally used as a tool through which colleges could give special consideration to racial minorities in order to help heal the effects of systematic and past discrimination. On June 4, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson gave the commencement address at Howard University preaching the benefits of this program: “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘You are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.”

For many schools, racial quotas were the means by which schools were able to remedy systemic discrimination. But that changed rapidly after an incident in 1978 at the UC Davis Medical School. This school had set a quota that reserved 16 out of their 100 seats for minority students. It was an effort to level the playing field.

Allan Bakke, a white male student, applied twice for the UC Davis school and was rejected both of those times. He decided to file a lawsuit that went to the Supreme Court. In this fateful case, the Supreme Court sided with Bakke, and ruled that schools across the nation were no longer allowed to implement racial quotas in their admissions process because they were considered unconstitutional and illegal.

The Court decided that colleges could only consider race on the basis of diversity on their campus, and that race could not be considered to remedy past discrimination. Societal discrimination did not “justify a classification that imposes disadvantages upon persons like respondent” (Justice Lewis Powell). Colleges could not use racial quotas to increase diversity, instead they had to set “concrete diversity goals.” The result of this Supreme Court case was not just the admission of Dr. Bakke to UC Davis, but also the decline of minority representation across the nation in prestigious universities and colleges and the slow death of Affirmative Action. Bob Laird, who was the head of admissions at the University of California, Berkeley between 1993 and 1999, said of the loss of racial quotas in college admissions: “The effects were really devastating, and Berkeley clearly began to lose the critical mass of African-American and Latino and Native American students that the campus had achieved over a number of years…And the campus has never recovered.”

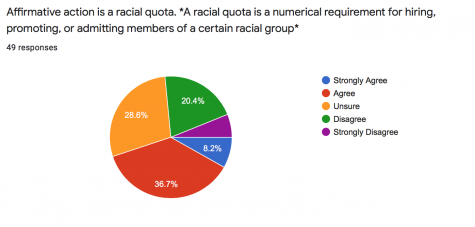

Out of the 49 HHS seniors that I surveyed, over 67.3% of them thought that colleges still use racial quotas to create diversity, and 44.9% of students thought that Affirmative Action is a racial quota.

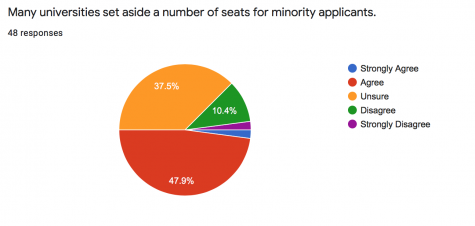

50% of seniors thought that many universities still set aside a number of seats for minority applicants. Although the act of using racial quotas in college admissions became illegal in 1978—almost fifty years ago—this perception of Affirmative Action still exists and continues to permeate the culture of HHS and other high schools.

Avanthi Chen, an HHS alum, said: “I didn’t really think about my race in terms of college applications that much until my white peers started talking to me about it. I definitely feel like the perception that I am getting a ‘leg up’ because I’m Brown is a white perspective and since [Hastings] is a primarily white institution, it kind of permeates my own thought a lot, and the thoughts of Brown students.”

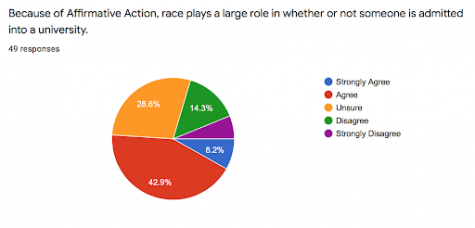

In 2003—the year most seniors were born!—another case (Grutter vs. Bollinger) which also scrutinized Affirmative Action was brought to the Supreme Court. The decision of this landmark case announced that colleges could now only consider a student’s race if it was a “factor of another factor,” like an extracurricular. In other words, a Black student’s race can only be considered if they participate in an extracurricular that connects them to their race, like being the president of a Black Coalition club. This is exactly equivalent to a college considering a student’s sexuality as advantageous to their application if and only if it is a “factor of a factor”—like if they were president of their Gay-Straight Alliance club at school. So why did 51.1% of seniors think that because of Affirmative Action, race plays a large role in whether or not someone is accepted into a university?

Our debates tend to paint a picture of Affirmative Action that just isn’t correct. There is no racial bonus or racial quota. It’s not about past societal discrimination. In fact, those are both now illegal in college admissions. Affirmative Action in our day and age is literally a “factor of another factor”—it’s equivalent to being the president of the GSA, the captain of the basketball team, or the president of the debate team. But the difference—and uproar—seems to caused by peoples’ uncomfortability with the fact that Affirmative Action is explicitly about race.

In the 2003 Supreme Court case, former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor famously wrote that within 25 years, race-based Affirmative Action would become obsolete and completely disappear. The majority of the Supreme Court justices who voted in this case agreed that Affirmative Action in its entirety would be illegal and virtually eliminated in the next twenty-five years. These SC justices thought it would no longer be necessary to promote diversity after 25 years and thought that a “colorblind” policy would replace it. As more and more Affirmative Action cases go to the Supreme Court, it is truly likely that Affirmative Action will soon no longer exist entirely, which is highly ironic as schools preach more and more about viewing a student holistically in their application.

But Affirmative Action could even disappear sooner than 2028. In October of 2008, the Supreme Court heard a case brought by Abigail Fisher, who is white, in which she argued that she was denied admission to University of Texas at Austin because of her race. Of all the justices who voted, Justice Ruther Bader Ginsburg was the only one who did not vote in the 7-1 vote in favor of Fisher. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote a dissenting opinion in which she argued that the Equal Protection Clause did not require that state universities be blind to the history of overt discrimination. She also argued that it is imperative that colleges explicitly include race as a factor in admission decisions rather than try to obfuscate its role or code race. It seems that Justice RBG’s idea of what Affirmative Action could look like is gone, and might never return.

Bob Laird said: “We’ve gotten ourselves into this kind of absurd position where we say as a society, by and large, we really value the goal of racial and ethnic diversity… However, we are not going to consider race and ethnicity in order to achieve this racial and ethnic diversity.”

Avanthi Chen noted that the perception of Affirmative Action for many people is that it is a “racial bonus,” and yet people often forget that there is an “Affirmative Action for white people, it’s called generational wealth and generations and generations of power and privilege and money. Everything that my family has earned has been in the last 20 years because we don’t have that ‘leg-up,’ and that in of itself is an advantage.”

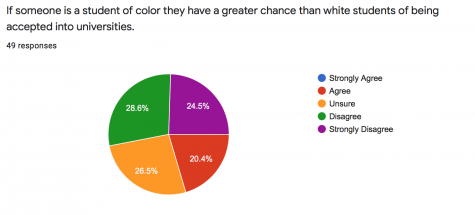

The argument of unfairness also tends to be attached at the hip to the idea of “reverse discrimination” or “reverse racism.” 8.2% of seniors thought that Affirmative Action is reverse racism, and 14.3% of seniors thought it was reverse discrimination.

20.4% of seniors also thought that a student of color has a greater chance than a white student of being accepted into universities. Avanthi recalled an incident in HHS when she was discussing college applications during lunch with her friends when one of her white friends said, “You’re lucky, though, at least you’re not white.”

Opponents of Affirmative Action say that any policy that considers a person’s race violates the 14th Amendment, which says everyone is guaranteed the “equal protection of the laws.” But does this mean that admissions officers shouldn’t take into account if someone is president of the GSA? Captain of the basketball team? Naturally gifted in music? Where do we draw the line? For what it’s worth, the Supreme Court has ruled time and time again that being inclusive does not mean that we have to be colorblind. Creating a more inclusive system requires that all of us recognize the role of race and privilege in America.

Affirmative Action is a big topic, and there is a lot more to uncover. I will be writing a series of articles in the near future about this, so if anyone would like to share their thoughts or have had personal experiences with it, please email me at [email protected]

Thank you!